THE EARLY YEARS WITH BLACK STAR, 1955 TO 1966

Don was born in Smithfield, Tennessee. The family moved to Murfreesboro, Tennessee, South of Nashville, shortly after being born. “Good ole’ home folk,” is what you would say about the Rutledges. They lived on a farm where they all worked together as a family. Growing up in rural Tennessee is where Don was exposed to the world. Don’s family was involved in the local Baptist community church, where they often prayed for and listening to missionaries from all over the world. Although this family was in the country, they were not limited. This world vision is what would drive Don throughout his life.

One of Don’s uncles had a box camera. Don asked if he could use it. He bought some film at the local drugstore and returned to the farm to explore his home with a camera. Don took many different pictures of the farm while he was a teenager. Having these photographs developed, he started to see the mysterious power of the photo.

While attending Temple College in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Don took photographs for the student paper and yearbook. This experience helps to build his technical skills and proficiency with the camera.

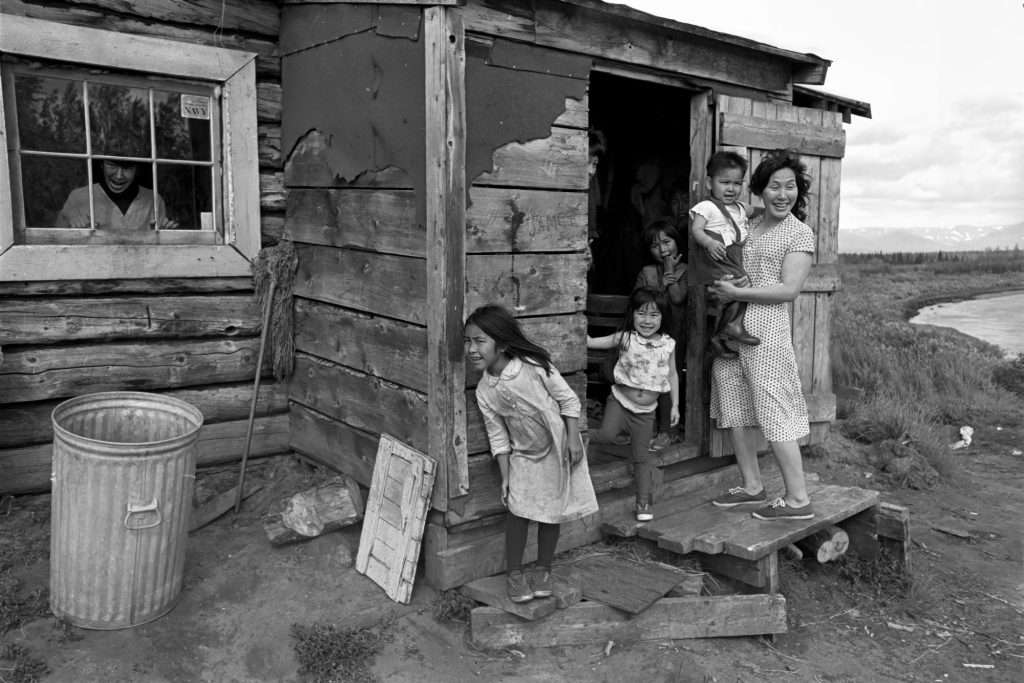

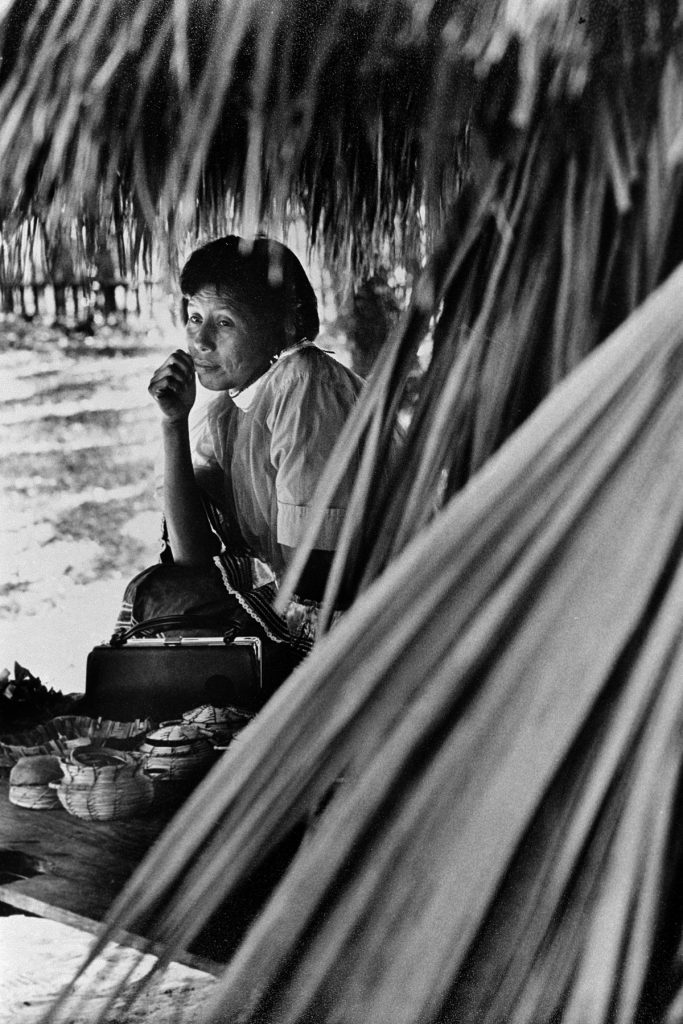

During the summers Don went on mission trips to help missionaries in places like Central America. Recording these visits with his camera, he then would show the pictures to his church and other groups.

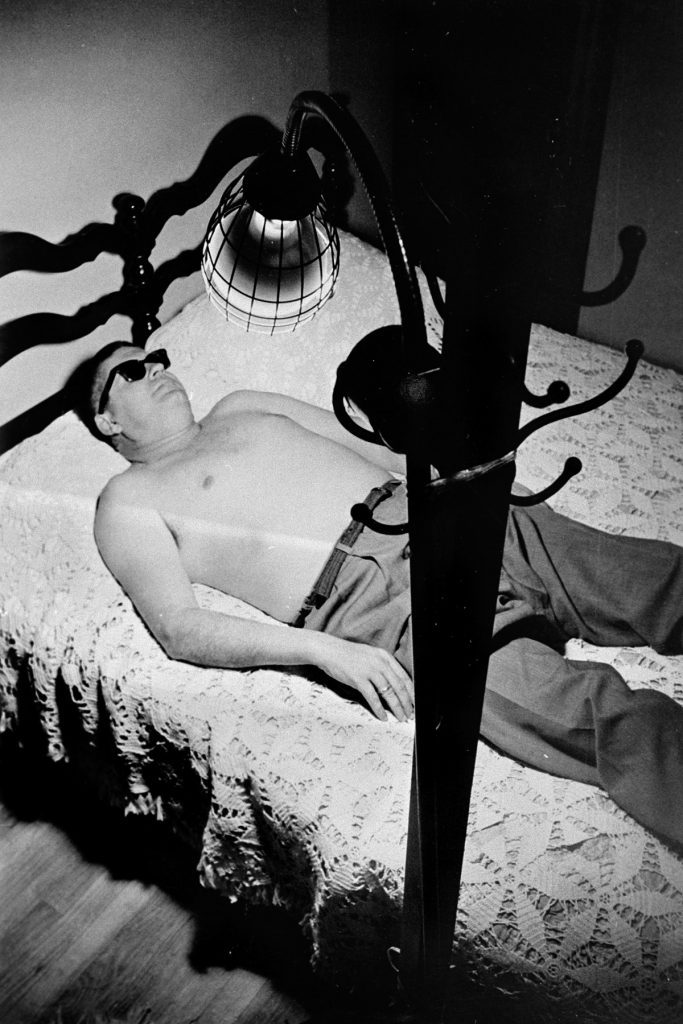

They enjoyed the photographs and were “transported” from Tennessee to Central America through the “eyes of Don.” Don was always pulling for the underdog since he could relate. While in high school, some boys jumped Don and seriously hurt him. He had been wearing braces at the time. His mouth was beaten up outside and inside. He later found each of the boys alone and repaid the favor. He knew very well what it was like to be a minority in number. This experience taught Don that there are times when people need others to help them.

Don’s helping nature moved him into the ministry. Don was answering the call to the ministry that he felt deep inside of himself. After talking to church leaders, Don was led to believe that the only place that he could serve as a minister was as a pastor or a missionary.

Don Rutledge majored in religion and psychology in college. These two give Don the edge in understanding people. Theology is centered on relationships. The Bible teaches us how God wants and desires a relationship with his people. We also learn through the Bible about the relationships between people. Nurturing each other as believers and reaching out to God’s world is what the Bible teaches. Jesus said,

“For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.”

Then the righteous will answer him, “Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink? When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you? When did we see you sick or in prison and go to visit you?”

The King will reply, “I tell you the truth, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers of mine, you did for me.”[1]

Don’s life reflects this passage.

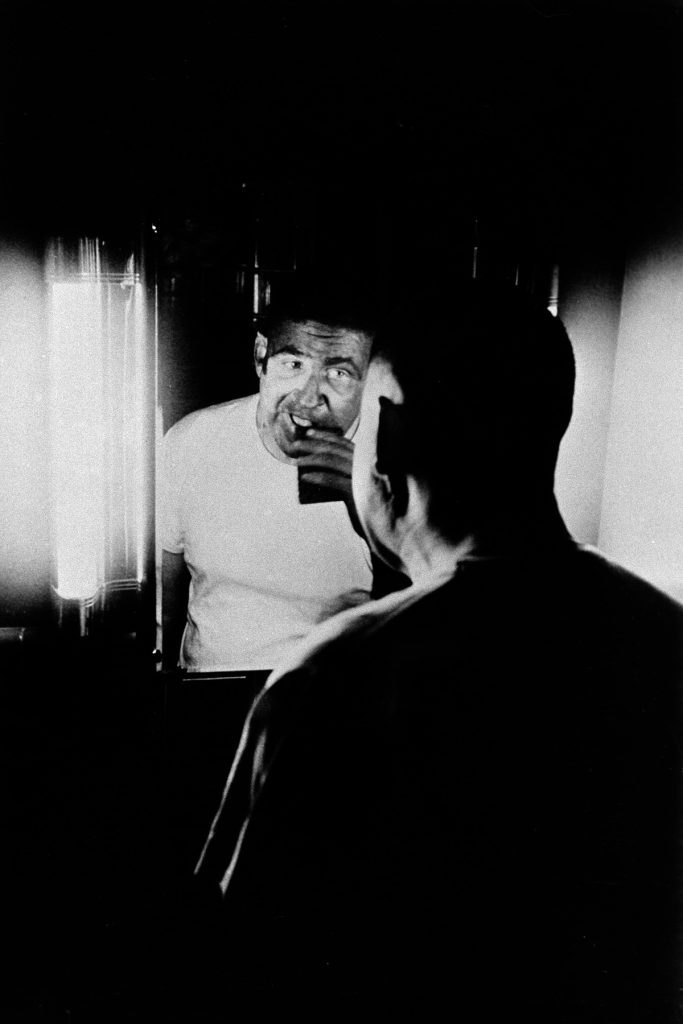

Psychology taught him how to read body language. Body language is critical in Rutledge’s photographs. Body language is more than peak actions of anger, sadness, or happiness. It runs the full range of emotions. The theology and psychology become so integrated in Rutledge’s work that it is difficult to separate them.

Don wanted to help people in need and aid them in acquiring dignity. Through preaching, Don tried communicating with people but was never truly comfortable in the pulpit.

While at Temple College, Don served as president of the student body. He was a rapid thinker in his own right. Don grew up in the most conservative of backgrounds. Like many from this traditional background, Don saw some of the faults of this thinking. Later, Don would see that very few groups have it all together. Throughout college, Don started trying to find his niche in society.

After graduating, the Director of Missions of Murfreesboro Association in Tennessee asked Don to consider pastoring a church. He talked to Don about how the church was falling apart. Going into this pastorate, Don planned to help the church close its doors. Coming from a very conservative group, where most pastors ruled with a specific authority, Don took a completely different approach. Don encouraged the people to grow as individuals and as a group. He let them take control of the church. The reason for this “hands off” practice was twofold: (1) Don did not believe in telling people what to do, and (2) he was pursuing a career as a photojournalist during the week.

Being a bi-vocational pastor allowed Don to combine two loves. Don was fulfilling the call to the ministry and was trying to understand this call of photography.

In 1955, Don frequently wrote Howard Chapnick at Black Star, a photo agency in New York. Don had noticed the photographers’ magazine cut-lines and that Black Star represented many photographers. Black Star told Don they wanted to see a portfolio before giving him an assignment. Don didn’t have a portfolio. When Don was corresponding, he gave them story idea after story idea.

Black Star was frustrated with the person who kept writing them so often. He had some excellent ideas, but can he take a photograph? They wrote back, telling him they liked one of his ideas. They contacted the parties to see if they were interested. That first story was for Friends magazine. This was the magazine of the Chevrolet Company.

Don was so delighted with the response that he immediately contacted the people in the area for the story, went and shot the story, wrote the material, and sent the package of contact sheets and material to Black Star. Black Star was quite upset. “We haven’t even talked to them, and you have already shot the story,” was the reply Don received. They also informed him of the many holes in the story and how it would not work. This was their mistake.

Don contacted the people again and went back, filling in the holes. This was Don’s first time to have someone critique his work and guide him. The Friends magazine liked the work and wanted to use Don again. This began a close relationship with Don with Black Star and even more with Howard Chapnick.

Meanwhile, Don’s career with Black Star was growing, and so, too, was the church. Don’s leadership style, which required all the people to become involved, saved the church and helped it to become a strong church of the community. Don realized that the church needed someone full-time. Don joked with the people, saying that when he was gone doing an assignment, and another person filled the pulpit, the attendance was always higher. Don felt more at ease as a photographer and less content as a pastor. Don resigned, and the church today still has good memories of Don. They continue to invite him to speak at homecoming.

Living so close to Nashville was ideal for a photographer: Black Star needed to cover the Grand Ole’ Ole and special cover coverage of the personalities in the Nashville area. Mirror magazine had asked Black Star to find the next—and—coming country star in Nashville.

Don was given the assignment. Don asked around about how to find someone who would know about the up—and—coming stars. After searching throughout the Nashville area, Don was told about a man who gave pens to those stars that were up and coming. This man was supposed to be the best at spotting new talent. The man happened to be under Don’s nose all the time. The man who knew all the up—and—coming stars worked at the camera store Rutledge patronized. The man who had been waiting on Rutledge for years was the expert on the country singers.

After talking with this expert, Don went to this unknown country singer’s home and wondered if this person knew what he was doing. Don sat on a crate, talked to Loretta Lynn, and did the story. This interview is portrayed in the movie “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” Don helped launch Loretta Lynn’s career. Don photographed many of the stars of Nashville for Black Star.

Don did coverages for Black Star on religious subjects. He followed the Wycliff translators into the Amazon. He photographed a theater group at Georgetown College in Kentucky that painted their faces like stained glass. The story was again religious.

[Walker Knight, See How Love Works]

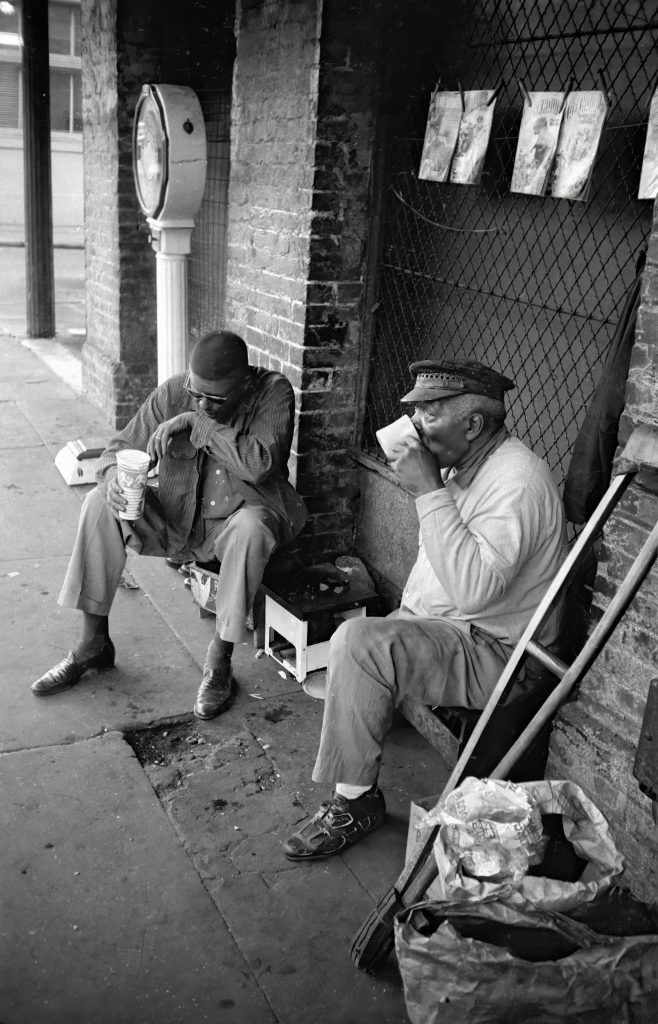

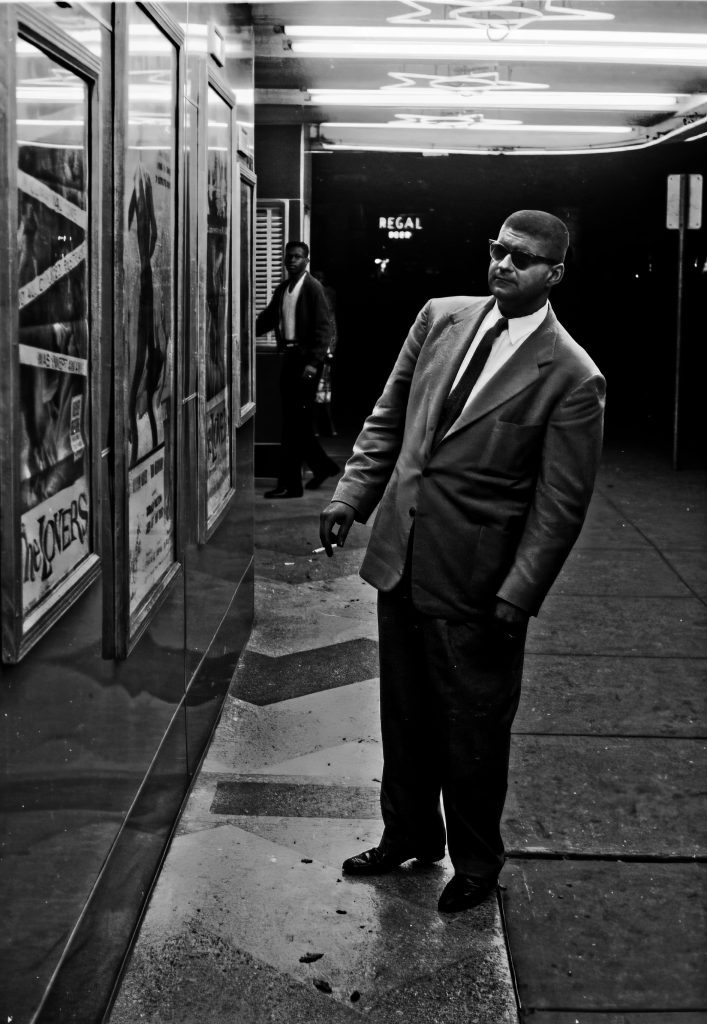

While Don had started working with Black Star, our country was in significant turmoil. Although Lincoln had helped to free the enslaved people, the Blacks were still in bondage in America. Racism had led the nation to the Civil Rights Movement. Don photographed Dr. Martin Luther King and other prominent people in the movement. His camera helped America to see itself in the mirror. Most of the country did not like what it saw. Don Rutledge helped America know how the South was an apartheid. Today, in South Africa, it is being played out again. But in the late fifties and early sixties, the United States had its insides turned out for the world to see.

Don was raised amid the racist environment of the South but was not at all a part of the oppression of the Blacks. Don was one of the most vital photojournalistic voices during this time. Don not only covered the news events but also created with a writer one of the most influential books during the Civil Rights movement: Black Like Me.

One day, while reading the newspaper, Don noticed an article about a street in Atlanta, Georgia, with more Black millionaires than anywhere else. How could this be? Black millionaires in the South? Don contacted Black Star to do a story on this idea. They checked their connections to see what magazines might be interested. They found a magazine based in Fort Worth, Texas, that was interesting. They sent the writer, John Howard Griffin, to work with Don on the coverage. While the two of them worked on the story, Howard Griffin talked with Don about an idea concerning the Civil Rights issue.

John Howard Griffin had the idea of taking some hormonal drugs that would alter his appearance, making him look Black. He also would style his hair differently to look as Black as possible. His idea was to cover the story of what it was like to be a Black in the South just from having a different skin color. This story intrigued Don. After completing the tale on the millionaires, John Howard Griffin and Don disappeared into the deep South to do the coverage for Black Like Me.

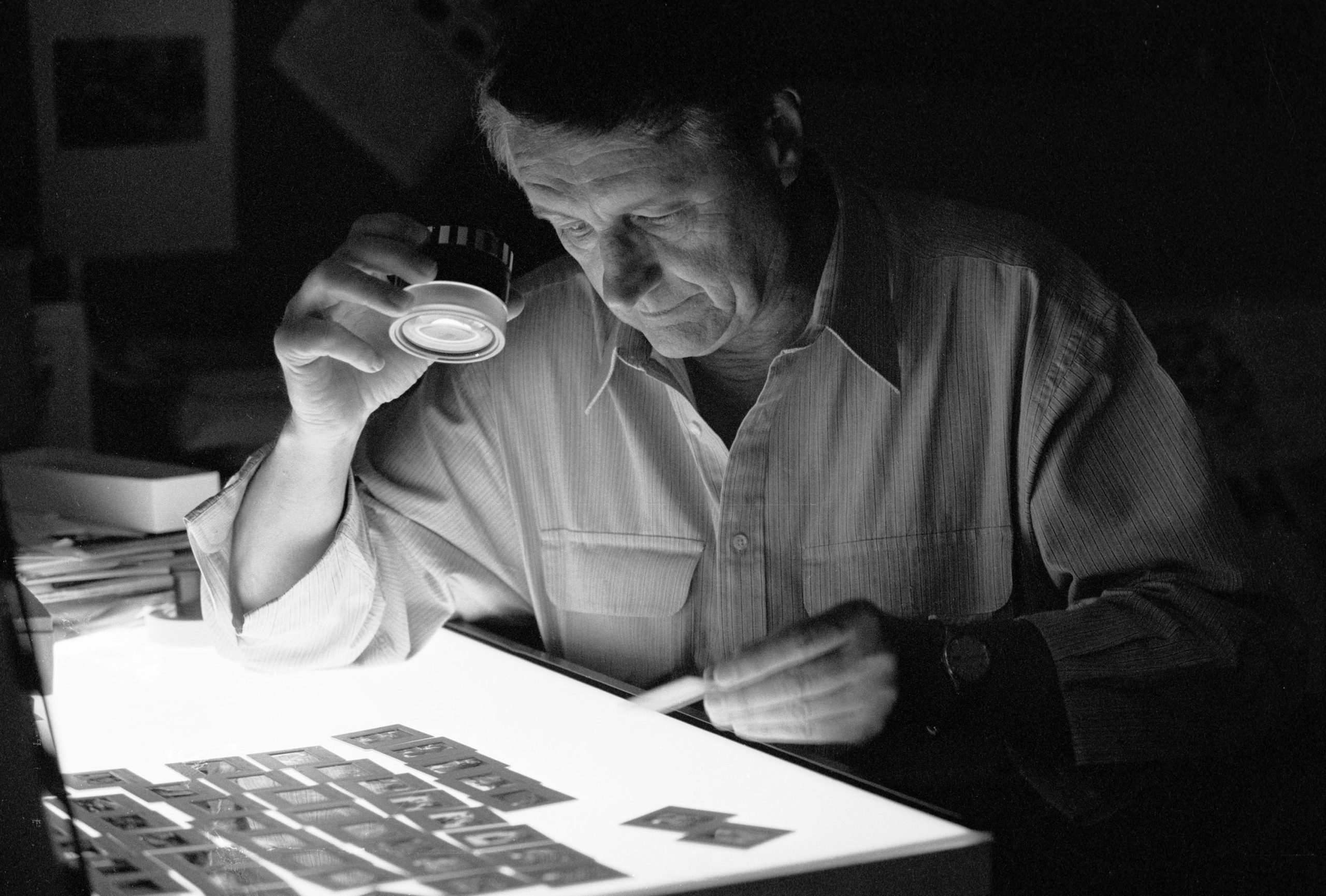

As they worked on the coverage, they returned the pictures to the magazine. This ensured everything was coming out fine and the cameras were working well. Howard Chapnick of Black Star told this story repeatedly to many photographers, emphasizing the difficulties one can encounter when working without a good agency. Don was not on staff for Black Star but was a paramount freelancer.

The magazine editor sent some of the photographs over the wire service before Don and the writer were ready for them to do so. This had editors all over the world calling, wanting the story. They were bidding for first rights to the novel. Black Star sold the book all over the globe. Then the publisher indicated that Don had committed to him all the rights. “This was what I thought was an unscrupulous publisher,” according to Chapnick.[2] There were meetings with Don, Howard Chapnick, and the publisher. The publisher said, “You are sophisticated urban New Yorkers, and I am just a country boy.” “Well, this country boy took us over,” remarked Howard Chapnick. “Because of his high sense of ethics, he didn’t want to battle the man for money. So all this good work that he did and our good work in placing the material all went for naught regarding Don’s financial return.”[3]

“His strength over the years was his high sense of ethics and his religiosity if you will,” commented Chapnick. “This carried through into his concern for humanity and the important issues. He tried to use photography to make people aware of the great problems in the world. He used it as a force for change, changing public perceptions and alerting the world to the problems that the world suffers like poverty and sickness.”[4]

“One of his great strengths is that he was very observant of the world around him, not only in terms of the big stories but the little stories, too. He had this happy faculty of being responsive to visually translatable ideas which could be made into saleable entities.”[5]

Don was concerned that the pictures were becoming more important than the story itself. Don gave the negatives to John Howard Griffin. The book came out. Don never received any royalties. The result was that Black Star had to provide all the money it had received to the magazine.

“Don was always good at providing background information and captions, and this is something that isn’t always apparent with a photojournalist. They tend to be pretty sloppy in adding the important words, which give more information than photographs, which sometimes are ambiguous. Few were as prolific as Don,” remarked Howard Chapnick.[6]

Eugene Smith could be considered to be Don Rutledge’s mentor in photography. Eugene Smith tried to capture with the camera more than just people as objects——he tried to capture the person’s essence in his photographs. Eugene Smith kept the dignity of those he photographed and made them heroes in the story. The subjects were romanticized by Eugene Smith. People, like the Doctor that he shot for Life magazine were always portrayed in such a way that the viewer identified with the subject.

Don studied photography masters and often quoted them. This was Don’s education——reading and studying the masters of photography and being aware of the world in which he lives. Being a Christian means growing in Christ. As a Christian matures, he should be able to move quickly into situations and respond with the heart of Christ. “One does not think during creative work any more than one thinks when driving a car. But one has a background of years——learning, unlearning; success, failure, dreaming, thinking, experience, all this——then the moment of creation, the focusing of all into the moment,” was the statement made by Edward Weston.[7]

Jesus looked at people as individuals——he saw the tree in the forest. Christians, too, must focus on the individuals in their ministry. Photographing people should reflect how one cares for people. “The photographer should not come to his subject with his image all fabricated in his head,” says Robert Doisneau. He continues, “The photographer must be absorbent——like a blotter, allow himself to be penetrated by the poetic moment, by the spirit of the place where he finds himself.”[8]

Don is true to the moment and never asks people to stage something. He may ask them to repeat something but never fabricate anything unnatural. “Nature has much more imagination than I have; why should I try to improve on it? The best I can do is to look for these manifestations and photograph them before they disappear.”[9]

Don believes that pictures are not merely to document an event or show what a person looks like but to communicate the essence of the event or person to the audience. “The best pictures are made by those photographers who feel excitement about life and use the camera to share their enthusiasm with others. The camera in such hands is a medium for communicating vital experience,” voiced Roy Stryker, editor of Life magazine.[10] For Ben Shahn, “Photography is a matter of communication in human terms and mostly in human subjects, and I have set this very simple problem for myself, of showing humanity in those terms that interest me and in the clearest way.”[11] Eugene Smith said, “The more important the story, the better the photographer should try to tell it. Even when the material is sufficiently important to make its impact regardless of the quality of my print, the more powerful the picture, the more certain I am that people will have a chance to understand what I want to say.”[12]

Jesus, rising from the tomb, was the culmination of the gospel. He defeated death. The choice of his words was so wise and timely. The Bible pictures important events as moments, not as long events. To me, photography is recognition in a fraction of a second, simultaneously of an event’s significance and the precise formal organization that brings that event to life.

The camera works fast, and so does the photographer. He must see, feel, understand, select, react, and act within the second. Movement and expression are unseen before it is stopped. A movement that never was and never will be again is captured.

All attention is concentrated on the specific moment, almost too good to be true, which can only vanish in the second that follows and produces an impact impossible with any staged setting.[13]

Photography has a unique power to awaken the social conscience. Suppose you are genuinely concerned with the plight of the people you photograph and are convinced that your photographs can do something——however slight——to help them. In that case, your sincerity and good intentions will inevitably shine through. This will help you secure from the people around you the cooperation that is essential if you are to produce good pictures.

On a practical level, try to be as sensitive as you can to the feelings of the people you are photographing or working with, and make sure your photographic technique reflects this sensitivity. Keep a low profile by using available light, not flash, and remember that many people are easily intimidated or antagonized by ostentatious display of photographic equipment.[14]

When Don’s colleagues are asked about Don and how he has impacted them, they all refer to his integrity. Don communicates well the idea of the eyes being the window to the soul. Maybe this is because Don tries to keep the innocence of a child when photographing. Don says,

Photography is a fascinating communications medium. It forces us to see, to look beyond what the average person observes, to search where some people never think to look. It even draws us back to the curiosity we experienced in our childhood.

Children are filled with excitement about their surrounding world: Why is the sky blue? Why is one flower red and another yellow? How do the stars stay up in the sky? Why is the snow cold?

As the years go by that curious child matures into a normal adult with the attitude of “who cares anymore about those childish questions and answers?” At that moment much of the world becomes mundane, little more than a place of survival until retirement and finally death.

But photography, in its best usage, will not allow us to do that. It forces us to continue asking questions which began in our childhood and probe for answers in the maturity of our life. The “seeing beyond what the average person sees” fills us constantly with excitement and allows us to keep the dreams of our youth. It gives “seeing” a newness and freshness as a person works hard to communicate through photography the messages that need to be conveyed.[15]

Don always tried to look at life creatively. Don took frequent rides into the country with his wife, Lucy. The writer and his wife would go along. Often, Lucy wanted to look through Don’s camera to see what Don was seeing. “He always sees something that I do not see,” was Lucy’s praise of Don. She enjoyed seeing Don’s photographs. Don says that she is his most prominent critic and fan. She can be so honest with Don, and Don listens.

For Don to be on the road and have two young boys growing up required Lucy to run the household while he was away and help make the transition when Don returned home. Things were not always smooth at home, but today, Mark, the oldest, is a missionary with his wife in Haiti. The youngest, Craig, works with the Home Mission Board in Atlanta at the main office.

Today, Don does not enjoy eating at fast food hamburger places; that was all he could afford for the first years on the road. Often, Don drove home several hours after a coverage to return early the following day because he did not have the money for a motel. For Don to make the pilgrimage that he did, he had to remain committed. He also had to have a real call, for the struggles were sometimes unbearable. Going from the pulpit to the streets of the world opened Don’s eyes and allowed him to see God’s world as a boy from the farm in Tennessee could have never imagined. Don’s coverages in the fifties and sixties helped pave the way for the coverages he would later request in the religious establishment. These years with Black Star they established him as capable of delivering. Don had a background that showed he had covered the top stories in the world. Even with this background, Don continued to struggle. Portfolio or no portfolio, his next stop in Atlanta tested his patience and endurance at wanting to be a minister with a camera.

[1] Matthew 25:35-40, NIV (New International Version).

[2] Mr. Howard Chapnick, interview by author, Tape recording, New York, New York, 12 October 1992.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jacob Deschin, 35mm Photography, (New York: A. S. Barnes and Company 1959), 14.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., 15.

[13] Ibid.

[14] George Constable, Photographing the Drama of Daily Life, (Chicago: Time-Life Books, 1984), 72.

[15] Don Rutledge, “Better photos for your publication or photography for communicators.” An unpublished article was given to the writer by Don Rutledge in 1992.