Getting started

“You need to take more photographs.” This is almost always my number one observation when viewing portfolios of students and emerging professional photographers.

Kodak has told us this for years. However, with film cameras, every time you pushed the button, money left your wallet on its way to Kodak, but no longer!

With digital cameras, it costs nothing to shoot all the pictures you could ever need of a subject. So why do so many people, even photography students, shoot so few photos once they have found a topic that interests them?

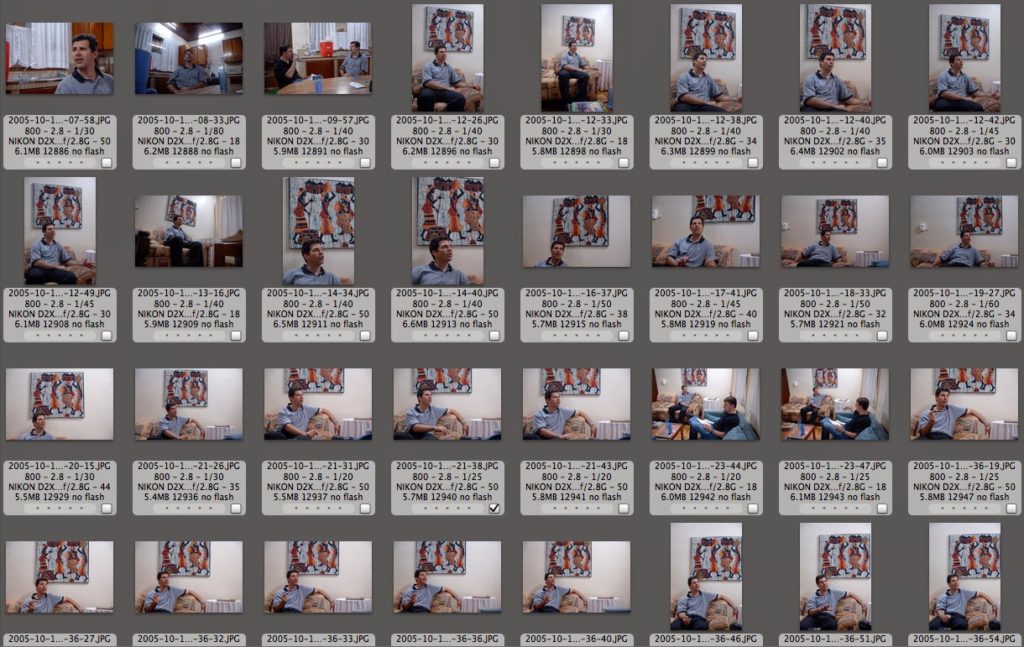

Back in the day of film cameras and contact sheets (an 8 x 10 sheet of all the photos on a roll gang printed), it was possible to see how a photographer thought or approached a subject. With good professional photographers, you could even chart the progression of creativity as the exploration of the subject plays out on the page.

First, there was a reasonably decent shot followed by similar shots improving on the first view. Next, the contact sheet showed a change in angle or lens and more exploration. Usually, about the third or fourth approach, the photos became more focused (pardon the pun) or fine-tuned. A few frames before the end of the roll would be the best one or two shots with an immediate and noticeable drop in creativity. The goal was met. The best photo had been made, and the moment was over.

The point is the photographer dedicated enough energy, time, and film to allow their creativity to kick in. Even with the best photographers, it takes a few moments and some thought for this to happen. It NEVER occurs if the subject that attracted the photographer’s attention, to begin with, is not given the energy, time, and number of photos to allow the necessary infusion of his creativity.

When you have a chance to see a documentary about a photographer working, watch his face. If you allow your creativity to join you on your photo shoots, you will see familiar expressions of thought, frustration and positive head nodding on the photographer in the film.

You’ve just seen in action what you would see on their contact sheet given the opportunity.

So many people see something that catches their eye and takes a picture. This is where most people start and stop – with one or two images (correctly called snapshots). The first view of whatever piqued their interest is rarely the best possible view.

Something piqued our interest in the play when we went to a show. Maybe it was the ads or reviews or friends’ comments. If our interest is high enough, we may buy box or orchestra seating so we can have a perfect seat, a seat where we can see the stage from the best angle, a center where we can see all the stage and be close enough to see the expressions of the actors’ faces.

In theater, the director uses lighting and staging to help drive the story’s message. The director “blocks” where he wants the action to take place on the stage. He directs your attention to where he feels it needs to be for the play’s impact.

Buying a seat for a play is like picking a good angle for making a photograph. Find a position where you have good light and can direct the attention of those who see the photos to what you feel has an impact. Now, make a few photographs and let the action build.

One of the digital camera’s most significant advantages is the ability to see what you just shot and the freedom to delete those you don’t want anyone to see.

To create your finest pictures, shoot until you feel (know) you’ve got it. That usually requires a lot of shots. This is not relying on the law of averages or luck. It is not like shooting a burst of photos with a motor drive hoping at least one will capture the moment. That is relying on luck.

By shooting ‘till you feel good about it, you have allowed your creativity to take over and guide your ability to see as only you can see.

Remember, if most people watched plays like they take pictures, they would leave the theater just as the curtain rises.

So shoot and shoot and shoot …