The making of great photographs requires an investment. We need a camera, computer, and software and, possibly, we need to attend classes to learn how to use all this equipment.

Should we buy a Mac or a PC? Which camera should we believe — Nikon, Canon, Leica, or Hasselblad? Which workshops or photo books do we require? We’ll need to read reviews of these products before making the investments.

However, the No. 1 investment a photographer can make isn’t about gear or training. Instead, it’s to invest your time and, as the Boy Scouts put it, “be prepared.”

Always Ready

National Geographic photographer Jim Brandenburg moved to the forest edge to have more time photographing wolves and other animals. He wanted to be ready when the time came to make those outstanding photos.

National Geographic photographers and writers usually spend three months on an assignment. Then, they take a break in the middle of the shoot, come home and review their work. The break gives them time to pause and reflect, so they can go back and fill in any gaps or expand parts of the coverage.

We can’t always devote three months waiting for great photo ops, but like Jim Brandenburg, we can be ready when the time comes.

How? By always have a camera with us.

Point and Shoot

The problem, of course, is that the size, weight, and bulk of the best-we-could-buy camera we own, not to mention the ancillary gear, can make that difficult.

That’s why many professional photographers have invested in point-and-shoot cameras. These small, pocket-sized cameras are as tiny as the old Kodak Disc cameras introduced in 1982. In addition, today’s point-and-shoots have resolutions rival the medium format film cameras, enabling you to enlarge to mural-size prints.

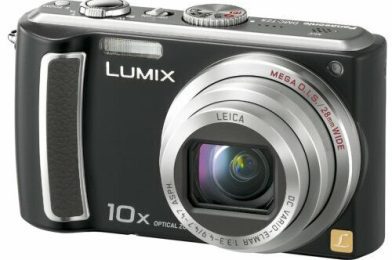

About a month ago, I bought a Panasonic Lumix DMC-TZ5 — and I have been busy learning all that it can do ever since. In the process, I have rediscovered the excitement I felt when I first began taking pictures.

It is so tiny; I now carry it everywhere. While waiting for food at restaurants, I enjoy playing with the camera’s macro mode. It is fun just photographing saltshakers and other small objects on the table. Discovering interesting compositions and watching how the light affects these objects is a joy.

The depth of field is much greater than with larger 35 mm digital cameras. For example, the ƒ-stop of the ƒ/3.3 on my little Lumix (wide open) compares approximately to ƒ/22 on a 35 mm.

Conversely, this little camera has a 10-to-one zoom! That’s equivalent to a 300 mm lens, which fits in my shirt pocket. A 300 mm lens for a 35 mm camera weighs six pounds and is over 10 inches long.

During the past month, I have wondered why I have all this professional gear—I can do so much with this little camera.

Pros and Cons

As I’ve used it more, however, I’ve gotten a clearer sense of the pros and cons.

For example, even with vibration reduction, these cameras are exceptionally tricky to hold steady. A tripod is a great help.

Additionally, obtaining a shallow depth of field is impossible for most of these cameras—my advice: learn to live with it.

The camera manuals are different from traditional cameras. You will need to read the manual and practice what it preaches using all the available functions to discover what each mode will do. These cameras have many ways that take some time to understand. Having said all this, I’ve found that carrying this camera helps me to see and take photos more often; it fine-tunes the eye.

Of course, carrying a camera all the time can cause some minor problems with your family. As my son joked last night as I took his photo at a restaurant, “It’s like having your paparazzi!”