Almond Standard built his log cabin home himself. It is located in Signal, Georgia.

[Nikon D2X, Sigma 15-30mm, ISO 100, ƒ/13, 1/4]

Group ƒ/64

In 1930 Willard Van Dyke, Ansel Adams, and Edward Weston formed the Group ƒ/64.

Group f/64 was founded by seven 20th-century San Francisco photographers who shared a standard photographic style characterized by sharp-focused and carefully framed images seen from a mainly Western (U.S.) viewpoint. In part, they formed in opposition to the pictorialist photographic style that had dominated much of the early 20th century. Still, they wanted to promote a new modernist aesthetic based on precisely exposed images of natural forms and found objects.

The term f/64 refers to a small aperture setting on a large format camera, which secures excellent depth of field, rendering a photograph evenly sharp from foreground to background. Such a small aperture sometimes implies a long exposure and, therefore, a selection of relatively slow-moving or motionless subject matter, such as landscapes and still life. Still, in the typically bright California light, this is less a factor in the subject matter chosen than the sheer size and clumsiness of the cameras, compared to the smaller cameras [35mm] increasingly used in action and reportage photography in the 1930s.

One of the magazines I have done work for through the years is Country Magazine. They require to shoot at the highest depth-of-field for their photos. To do this on today’s DSLR cameras, you typically shoot at ƒ/22. This would be equivalent to the ƒ/64 on an 8′”x10″ that many in Group ƒ/64 used.

The strength of shooting with sharpness all through the photograph is it puts the audience into the scene. This is where you use composition and lighting to draw the audience into the picture.

While your eye may go first to where the photographer directs you using light values and composition, your vision will wander around the scene as if you were standing there yourself.

This style was in opposition to the pictorialist of the time.

Pictorialism is the name given to an international style and aesthetic movement that dominated photography during the later 19th and early 20th centuries. There is no standard definition of the term. Still, in general, it refers to a style in which the photographer has somehow manipulated what would otherwise be a straightforward photograph to ” create” an image rather than simply recording it. Typically, a pictorial photograph appears to lack a sharp focus (some more so than others), is printed in one or more colors other than black-and-white (ranging from warm brown to deep blue), and may have visible brush strokes or further manipulation of the surface. For the pictorialist, a photograph, like a painting, drawing, or engraving, was a way of projecting an emotional intent into the viewer’s realm of imagination.

In photography, BOKEH is the aesthetic quality of the blur produced in the out-of-focus parts of an image produced by a lens. Bokeh has been defined as “the way the lens renders out-of-focus points of light.” Differences in lens aberrations and aperture shape cause some lens designs to blur the image in a way that is pleasing to the eye. In contrast, others produce unpleasant or distracting blurring—”good” and “bad” bokeh, respectively. Bokeh occurs in parts of the scene that lie outside the depth of field. Photographers sometimes deliberately use a shallow focus technique to create images with prominent out-of-focus regions. [Wikipedia]

I would say that those who shoot primarily wide open aperture are more stylistically like the pictorialist of the last century and less like Group ƒ/64 which was about preserving everything in the scene.

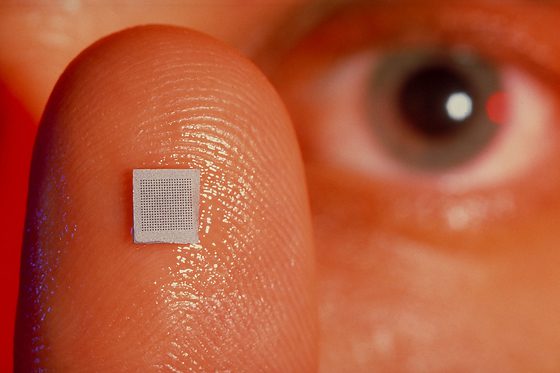

I love that my camera lets me shoot from ƒ/1.4 to ƒ/57. The ƒ/57 is when I shoot with my Nikon 60mm Micro lens. Here is a shot I did that was widely published.

“ƒ/8 and be there,” Alfred Eisenstaedt responded to the question on how to be a successful photographer.

However, the earliest record of the quote “ƒ/8 and be there” is attributed to Weegee, a famous street photographer during the 1930s, ’40s, and beyond. It represents a philosophy to keep technical decisions simple and be where your vision takes you. The quote has been the mantra of photojournalists, travel photographers, and even nature photographers.

This says you need to anticipate and be technically ready to capture “the decisive moment.”

I say to be careful not to treat your interviews as having microphone and recorder levels set and just hit record, and I am done.

Don’t Make Your Camera a Box Camera

Kodak made a box camera where you pushed the button, and Kodak did the rest. You had no control over the Aperture, Shutter, or even ISO.

Once you subscribe to shooting all your photos like the Group ƒ/64 or those doing BOKEH photography, you have essentially taken that costly camera and turned it into a box camera.

Exercise for you to do

Take your camera and just one lens. Find a scene, and then shoot the stage at every aperture you can on your camera. Now, as you get to a wide open gap, you know that your depth-of-field becomes very shallow, so remember to change your focus so that the focal point is on something in the scene that creates interest. We call this selective technique focus.

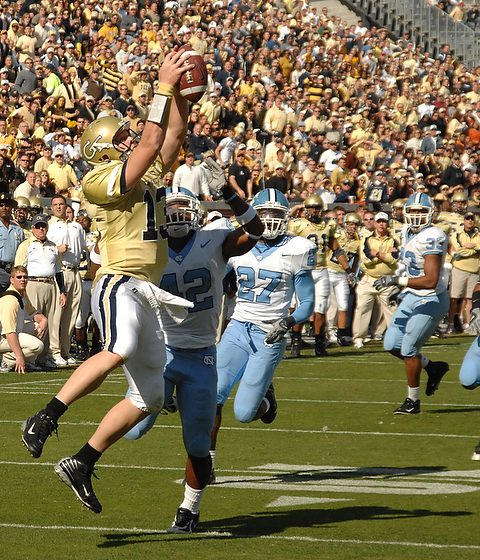

Now spend time doing this for several different situations. It might be able to do it with scenic rather than people at first but then move on to people. What is fun to do is to shoot where there are many people. A good example would be in a coffee shop.

Your challenge is not to make one good photo in each situation but rather a great photo at each ƒ-stop.

When you master this technique, you discover you can say something different about each situation. This will be the difference between writing a concise sentence and creating a novel with just one frame.

Will you take up the challenge?

I believe the great photographers are the ones that know when to use what aperture to capture what they want to say about the subject.