Martin Luther King, Jr. funeral. [photo by Don Rutledge]

When I reflect on what set my mentor, Don Rutledge, apart from other photographers, one skill shines above the rest—his extraordinary ability to contextualize. This wasn’t just about taking pictures but weaving together a visual story with depth, character, and narrative.

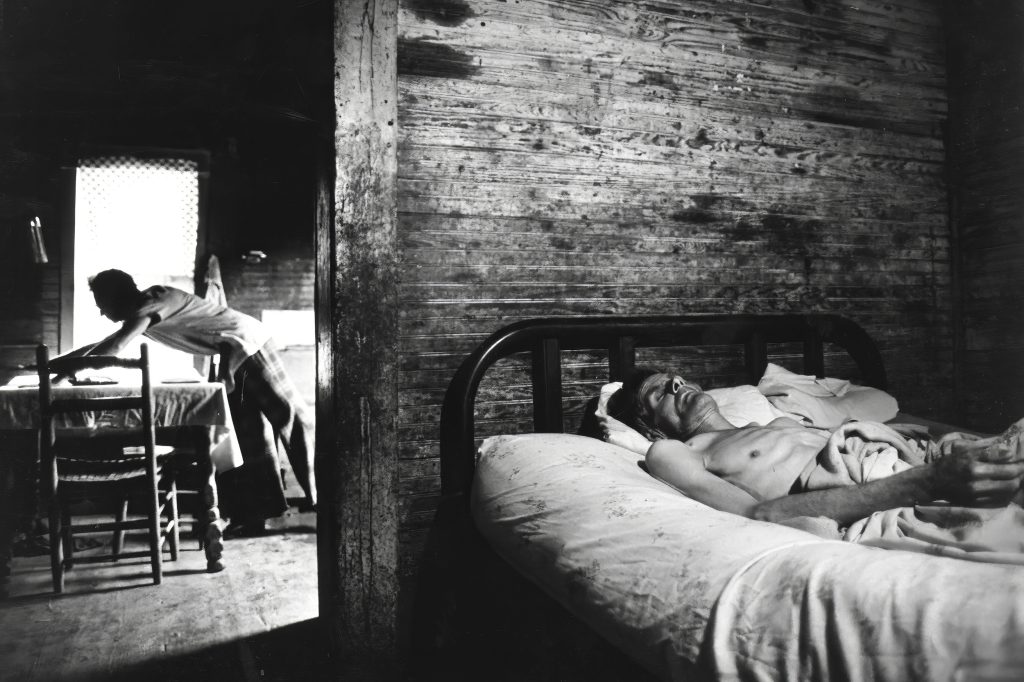

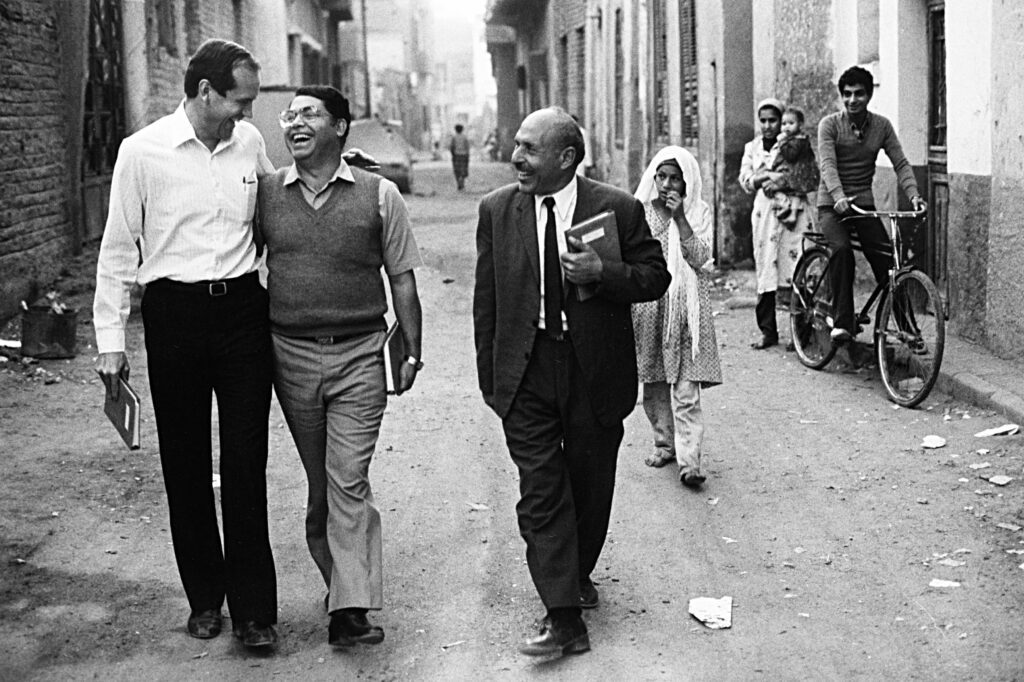

Many photographers understand the basics of environmental portraits—placing a subject in their natural surroundings to help tell their story. But Don took this to another level. For him, it wasn’t simply about a person standing still in a setting that described their profession or personality. It was about how that person interacted with their environment and how their surroundings shaped their narrative.

Don was always after the wider shot, not for the sake of showing more but for the sake of bringing a deeper context to his subjects. His mastery of composition meant that every object, every shadow, and every beam of light in the scene played a part in telling the story. He didn’t rely on isolated moments but instead captured the interplay between the person and their world. This connection, this broader story, made his photographs feel so alive and real.

His process was almost cinematic. Don approached photography with the patience and precision of a director, except he never directed his subjects. He knew that life would naturally create the needed moments if he just observed long enough. Rather than forcing a scene, Don learned to wait. And if the perfect moment didn’t come? He’d wait some more. He understood people so well that he knew their habits and behaviors would repeat themselves, giving him another chance to capture that elusive, perfect shot.

But it wasn’t just his patience and observation that set him apart. His understanding of context wasn’t about showing the big picture but about using the environment to add layers of meaning. Unlike an ordinary establishing shot, Don’s wider shots tell a deeper story—one where the viewer can almost step inside the frame and feel the relationship between the subject and their space.

Shallow Depth of Field vs. Depth of Story

In contrast, many photographers today rely on shallow depth of field to isolate their subjects. While there’s a place for that technique, it can feel like you might as well put the person in a studio with a muted backdrop when overused. Sure, the background becomes soft and discreet, but it also strips away the environment that could have added much more to the narrative.

Don’s approach was the opposite. He understood that depth of field wasn’t just a technical decision but a storytelling choice. Rather than erasing the background into a blur, he used a bit more depth of field to keep enough in focus to bring context. The surroundings weren’t distractions—they were essential elements of the story.

However, shooting with more depth in the field requires a different skill. It forces you to carefully compose your shot, working around the clutter and chaos until you can distill it into something beautiful and meaningful. It requires an understanding of light, lines, and placement—how to take what’s in front of you and mold it into a master painting where every piece of the scene contributes to the whole.

Instead of isolating the subject, Don used the environment to draw the viewer in, creating a relationship between the subject and their world. It’s a much more challenging approach, but one that, when executed well, leads to photographs that are rich in detail, layered in meaning, and powerful in their storytelling.

In an era where isolation seems to dominate photography, Don Rutledge’s ability to contextualize his subjects is a timeless reminder of what storytelling in photography can be. His work was more than just images—it was a narrative brought to life by his mastery of patience, composition, and context.

Steven Spielberg’s Mastery of Depth: Using Wide-Angle Lenses to Weave Context into Cinematic Storytelling

Steven Spielberg’s approach to depth-of-field, particularly with wide-angle lenses, is a crucial element of his filmmaking style. Unlike many directors who prefer shallow depth-of-field to isolate their subjects, Spielberg often opts for smaller apertures that allow for deep focus, where the foreground and background remain sharp. This choice adds layers of context to his scenes, making them immersive and rich in detail.

Spielberg avoids wide-open apertures and ensures that every part of the frame contributes to the story. For instance, in Jurassic Park, Spielberg uses a smaller aperture during crucial scenes, such as when the T. rex first appears. The terrified characters in the foreground and the menacing dinosaur in the background are sharply in focus. This technique enhances the viewer’s connection to the environment, creating a more realistic and engaging experience (Personal View).

Spielberg’s use of wide-angle lenses, such as the 21mm lens, is particularly effective for maintaining deep focus. By choosing these lenses, he can capture expansive shots, conveying a sense of vastness while keeping multiple planes in sharp detail. This technique was masterfully used in Raiders of the Lost Ark, where Indiana Jones and the surrounding environment are in focus, allowing the viewer to grasp the significance of the character and his surroundings (Wolfcrow) (No Film School).

By employing deep focus, Spielberg can add context that enhances the narrative. Rather than isolating his characters from their environments, he integrates them into them, making the audience feel like they are part of the world he creates on screen. This approach requires skillful composition and an understanding of how to naturally balance visual elements to guide the viewer’s eye through the scene. This mastery of context through depth-of-field and wide-angle lenses distinguishes Spielberg as one of cinema’s greatest storytellers.