Worship in Togo, West Africa. [Nikon D5, Sigma 24-105mm, ISO 8000, ƒ/4, 1/100]

Have you ever heard someone say, “Let’s get real here?”

Often in meetings and going about life, we are performing for others. We read the room and situation and plan how we will act. The thing is that organizations often take on this personality as well.

Organizations and people look to the audience they are playing for and try to figure out what they want to hear to get what they want, which is often a living.

Everyone longs for love, acceptance, and connection. We often do not know how to make it happen. We learn over time that we cannot manipulate people and try to pull people closer to us because that does just the opposite and pushes them away.

When we interact with authentic people, we feel we’re interacting with “real” ones, people free from pretension and without false fronts. For a group of people to experience authenticity requires leadership to foster a place where sharing their authentic selves will be welcomed.

A few years ago, when teaching at the end of the week, I shared a little about myself. When talking to the person who invited me later to review what I could have done better, he made a profound comment that changed my life. If you had let people know what you shared at the end of the week earlier, I think people would have connected with you more than they did.

The following year I started my week of teaching by being much more vulnerable. I told the class my life story and growing up with autism.

Organizations can do the same thing in their communications by being authentic with their audience. One of the best approaches to achieving authenticity is photojournalism.

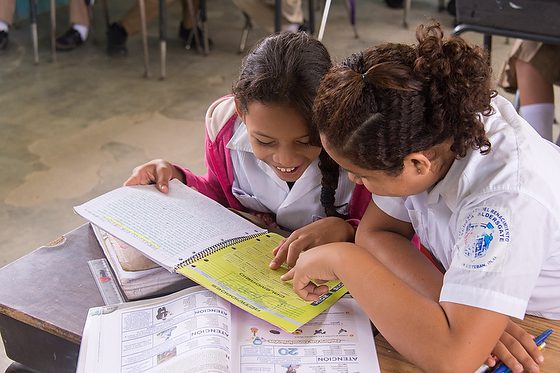

Still, the photograph stops time. It gives the viewer a moment to think, react, to feel. When the camera captures a “real” moment in time rather than one that is “setup,” then the power of that moment gives validity to the storyline.

The viewer often cannot know if a situation is actual or not, so it is up to the photographer to be sure that they have a moral compass that guides them to remain truthful. All it takes is for a photographer to manipulate one image, and then all their work is called to question.

Many nonprofits and businesses use stock photography for their communications. It is often more about convenience than any other reason that they choose to use a photo that isn’t about their organization to communicate some of what they do.

There have been numerous times when competing organizations use the same stock photo. The same image of a person carrying a laptop was used by competing computer companies. Different insurance groups used the same picture. Just google “same stock photo used in two ads” and look at all the examples.

My friend Gary S. Chapman encourages those organizations he works with to hire him to create real moments. He also encourages them to use his byline. “Photo by contributing photographer Gary S. Chapman” gives authenticity to the photo and helps people know it isn’t a stock photo.

I suggest finding stories that reflect what you do for people. Once you find that story, I would assign a journalist team to cover the story. The unit can be a photojournalist who writes and shoots or a group consisting of the writer and photographer. You may even choose to use video as well.

It would help if you gave them the time to “peel the onion,” which is getting to the deeper story so that they can inform your audience how your organization made a difference in their lives.

I would find a few stories and have them cover all of them, so you have a series that helps validate your actions in people’s lives.

I have found that those organizations who talk about how they have made mistakes early on and are constantly correcting to do a better job will win over their audience.

I loved how the organization Honduras Outreach or HOI told their own story about a kiln they bought for the people in the Agalta Valley of Honduras.

The people in Honduras asked what are they do with the kiln. Well, you make pottery and sell it to the tourists.

A couple of years later, HOI noticed that the Hondurans had been making donut bricks that they used to create chimneys for the stoves in their homes. They then started making tiles for their homes and schools with the kiln.

What I love about the story being told is that HOI admitted that they learned that they were not the ones coming to help out these helpless and inferior people. The people of Honduras were brilliant and creative. While they couldn’t have made the stuff they did without the kiln, they also knew that making pottery for the tourists didn’t make sense. There just were no tourists and just the volunteers coming to work in their communities.

This story helped HOI be more authentic with its audience. It enabled them to get more people involved.

There are times when you may need to set up a photo. Sometimes for the safety of the people involved, you cannot get a picture. You may choose to set up a shot for illustration purposes. This is OK, but you must tell your audience you did this. Credit the image as an Illustration, and where it is possible, explain why you chose to illustrate the photo.

Sometimes, in the caption of telling why you had to do a setup photo, you help the readers understand why you need their help.

Today’s young people are looking for authenticity. They want to work with organizations whose words match up with their actions. The most robust way to communicate authentically is to use photojournalism.

Are your communications grounded in a moral compass?