Here is an example of the photo the grandmother showed me on the plane, except I am closer than she was with her camera.

While flying out of Dallas, I was sitting by a sweet little grandmother. She had been visiting her grandchildren and was eager to talk about them. She showed me a snapshot of a red dot in the middle of someone’s front yard. The red dot (at least to her) was a compelling photograph of her granddaughter in a little red dress my new friend had made for the child.

All I could see was a red dot, but the grandmother could see the beautiful little girl and her handmade red dress in her mind’s eye. If I had made photographs like that one while I was on my assignment, it would have been the last time I ever worked for that client!

That grandmother held a snapshot that was a memory jogger for her and those who already knew the little girl. A photograph that can communicate to anyone is something else altogether.

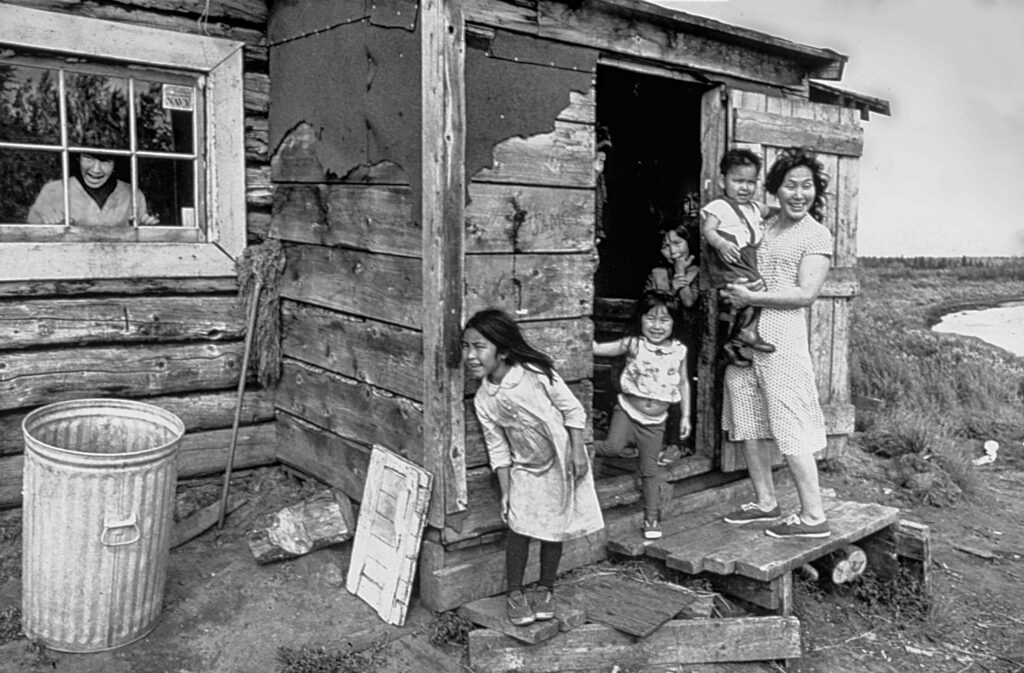

If my assignment had included that child, I would have needed to show the cute little daughter up close enough for anyone to see how charming she was, and perhaps through body language, the child could let the viewer know how proud she was of her new dress.

I believe there are two main reasons people make photos:

- People take pictures to please themselves

- People take pictures to communicate something to others

Making photos for ourselves is pretty straightforward. We know right away if the image was successful. Either we like it, or we don’t. If we don’t like it, we can probably figure out what would make it better. Photos we take for ourselves belong to the category of snapshots. They are intended for the family photo album to hold memories of vacations, birthdays, and other of life’s special events.

One year I decided to help my father transfer the family movies to video. It was a pretty simple setup, but it worked. We projected the film onto a screen and videotaped them while our family watched the old movies. The video camera captured our comments as we watched the old films. The funny thing is that every time we watch these videos together, the family makes the same comments, and we laugh at how these old pictures always trigger the same responses.

As I think back, I realize that the older films, the ones made before I was born, don’t do much for me. You just had to be there for these snapshots to work.

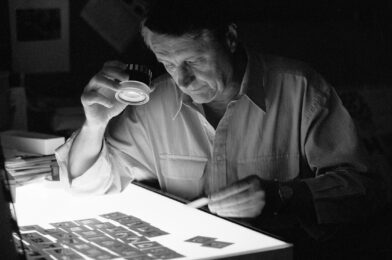

Okay, so if we want our photos to communicate, we must consider another person’s point of view. So how can we attract and hold the attention of our audience? One way to learn this is by studying the work of photographers whose work does just that.

I suggest aiming for the top. If you like sports, then open Sports Illustrated and study the photos. Ask yourself and others why these photos work if you enjoy traveling photography; learn about National Geographic, Southern Living, or other magazines that do a good job keeping paying audience.

Some key elements keep the viewer’s attention. Editorial photographers try to stop the viewer with their photographs. They want the photo to spark curiosity, to make us read the caption under the picture. A good caption will make us want to read the story.

Here are some of the critical elements that distinguish a good photo from a snapshot:

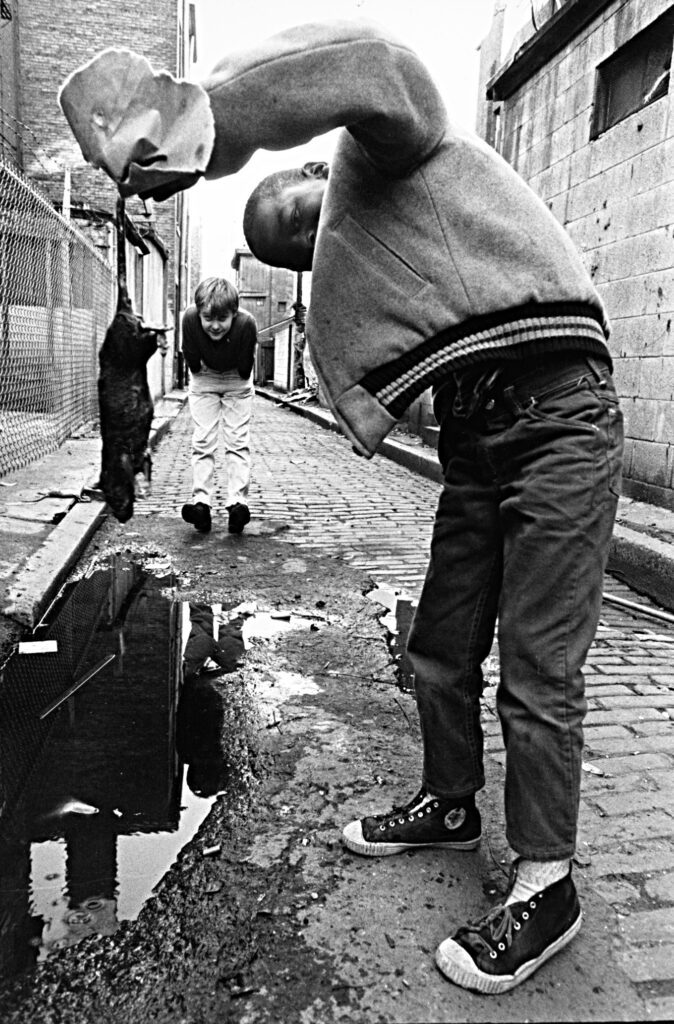

It is stopping power. The world is full of visuals vying for our attention. There are photos on products, TV, magazines, newspapers, the web… everywhere, pictures, pictures, and more!

I believe the key is to show our audience something different. We take most snapshots from standing height and way too far away. Get down to the ground for a worm’s eye view or get up on something for a bird’s eye view. Get a lot closer. Closer will give our photo a little stopping power. It’s out of the ordinary. It’s a surprise.

Communication of purpose. Engaging with content is the goal. People want to be amused, entertained, or learn something from a photograph. We need to think about why we are taking a picture. If we aren’t sure, no one else will be either, and we’ve made another snapshot.

Emotional impact or mood. Some folks can tell stories better than others. The same is true with taking photos, but we will make better photos if we consider how to bring more drama into them. The key to creating emotional impact is first to experience the emotions we wish to convey. We need to have a genuine interest in the subjects we photograph.

Our photos need to be technically correct, that’s understood, just as we expect a musician to at least play the right notes. But if the image doesn’t draw the viewer in and move them, it’s like listening to a machine perform Chopin. What we choose to include or exclude makes up the graphical elements that can catch the viewer’s attention.

Remember, a technically competent photograph often is no more than a technically competent snapshot and quite dull. Of course, we must be sure the camera’s settings are correct, but this is only the beginning. We need to look for a new perspective, look for another point of view so that people will want to see more of our pictures rather than looking for ways to get out of enduring more snapshots.