I have talked about shooting enough photos of a subject to allow our imagination and creativity to kick in. Now that we are all doing just that (making plenty of pictures every time we approach a subject), we can see how even a millimeter’s change in angle can make the difference between a good and a great photograph. Or, for that matter, it doesn’t take much to make the difference between a good shot and a crummy one.

If we print all the digital images from a shoot as large thumbnails, we’ll have several pages of images we can study side-by-side. This should give us some insight about our work that is looking at our photos one at a time will never give us.

Editing software like PhotoShop allows us to rate photos from zero to five stars. Here are some guides to use as we look to see if we have any FIVE STAR photos in that shoot.

Exposure. Not just the technically correct one, but the proper exposure for the effect we wish to convey. We can under-expose a little to emphasize graphics or over-exposed (this is done a lot in fashion photography to diminish skin tones or to highlight eyes and lips).

Focus. I love selective focus, where the depth of field is very shallow. This lets me direct the viewer’s attention to where I want it to go. It makes the subject pop out. We see this used in fashion and sports photography a lot. Just the opposite (a deep depth of field) may be just what is needed in landscape photos, and indeed, it is a necessity in macro photography.

Anytime we make someone feel as if they can see into our photography, we have accomplished something. After all, it is only a two-dimensional object.

Composition. Medical students are told, “First, do no harm.” Photographers should take the same advice and leave out all unnecessary elements. All composition is the selection of what should be in and out of the frame when we release the shutter. Speaking of framing… to add depth to a picture, frame it as you take it. Shoot under the branch of a tree or through a door or window. A frame is only one of many visual elements that can draw a viewer into our photo. Elements like leading lines will give it a three-dimensional feel.

Anytime we make someone feel as if they can see into our photography, we have accomplished something. After all, it is only a two-dimensional object.

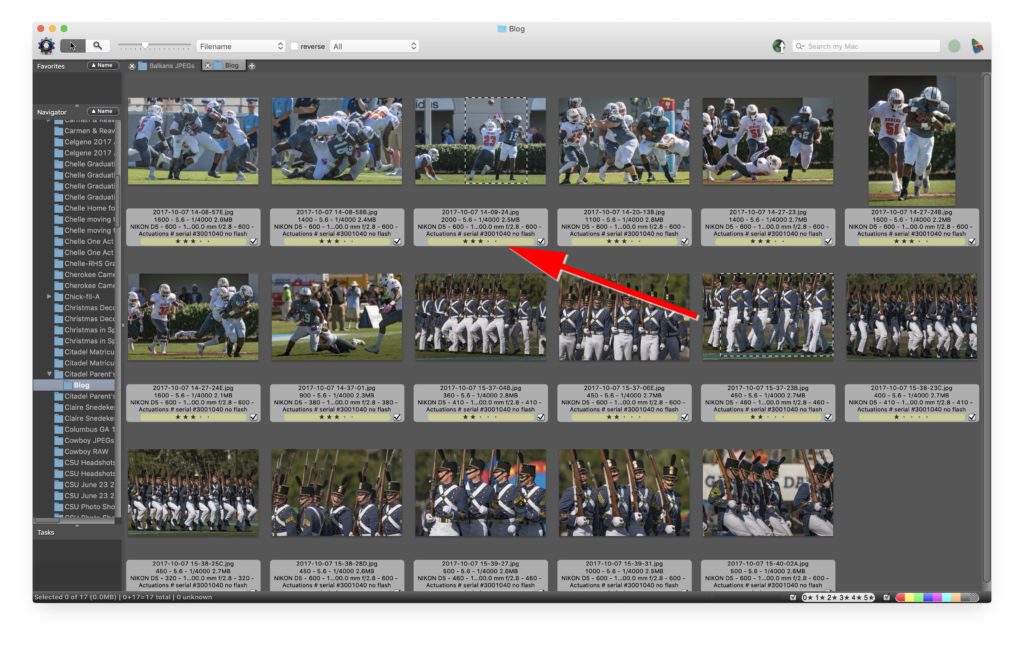

See how the feet are cut off.

The Citadel [NIKON D5, 85.0 mm f/1.8, ISO 100, f/7.1, 1/320]

We can include the feet and anchor the photo, barely moving the camera.

Lighting. Light can draw one into the photo, too. Light is probably the most dramatic, mood-setting tool we have as photographers, next to expression and body language. The color temperature can be powerful. The warm late evening light, the cool early morning colors, or the green cast of fluorescent office light each carries a mood of its own.

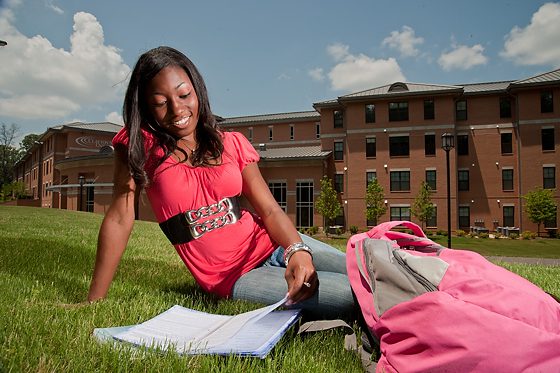

Expression. Realtors like to say what matters is location, location, location. Portrait photographers KNOW that the composition may be beautiful, the lighting creative, the clothing and background perfect, but if the EXPRESSION isn’t what it needs to be…. No sale! Is a smile what is needed? (By the way, NEVER tell ANYONE to smile.) Most adults can’t turn it on an off and kids will come up with some rather unusual expression, but generally NOT a real smile. If, as a photographer we need the to smile – naturally – then it is up to us to elicit one from them. We owe them that. After all, we ARE the photographers. Usually pictures of people should show their faces. Sounds obvious, but if our subjects are watching something happening, say a ball game or a birthday party, we must be sure we are not so distracted by the event that we forget what is important… our main subject, the faces of our subjects.

Body Language. We can photograph someone several feet away (and not even show their face) and still communicate much about them if we watch their body language. Watch their arms. It’s incredible what we say just by the position of our arms. Do our subject’s arms communicate what we want? Are they open or closed? Is the person in our photo leaning forward or backward? Does their position engage or pull back? Do they appear to be sensitive or cold? Are they reaching out to another or pushing them away?

The Eyes. An eye doctor may tell us that the eyes don’t change. Perhaps that is true in a technical sense. Be that as it may, watch the eyes. They describe it all! However, it happens the eyes are the essence of a portrait.

The Head. A millimeter’s turn of the head and a slight tilt is all it takes to distinguish between zero and five-star photography.

This is in no way a comprehensive list; it is only a sampling of many things we must consider when “grading” photos.

By moving the camera merely a millimeter, you can include their feet rather than chop them off, leave them out, or have another person change the mood.

A millimeter can keep the tree from growing out of your spouse’s head. Moving an inch to the left may let the camera see a person’s face better or distinguish the main subject from their surroundings.

When we shoot enough photos, we see the difference that just a millimeter’s change can make. Then we will begin to see why one image is terrible and another is good.

In the Olympics, the difference in millimeters determines who wins and loses a race. In photography, it can be what differentiates a great photo from the others.