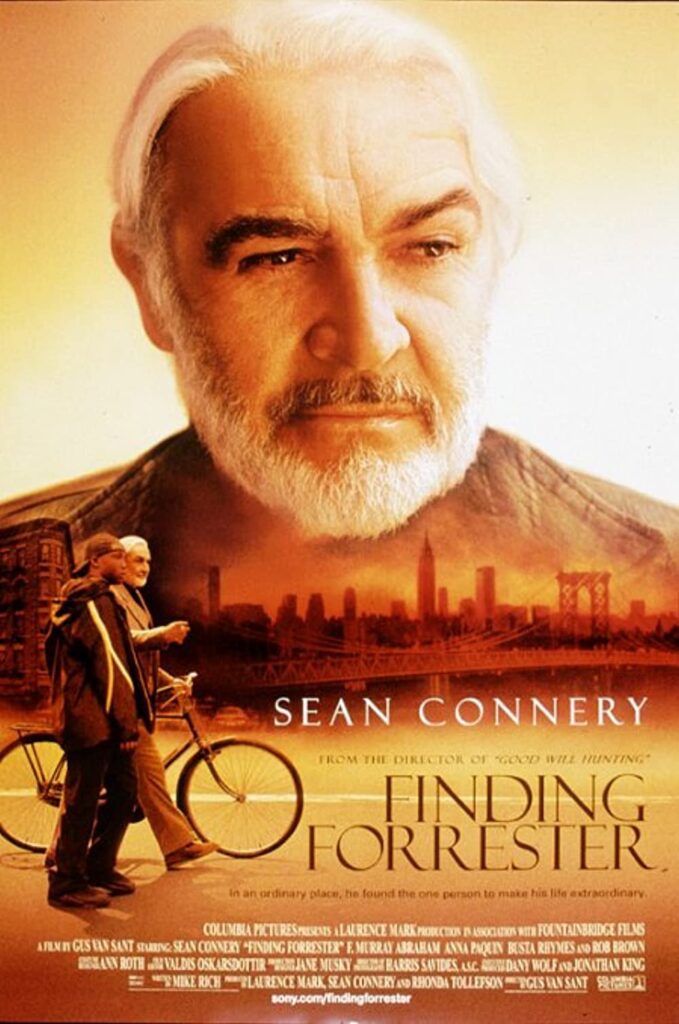

Finding Forrester is one of my favorite films. In the movie, William Forrester, played by Sean Connery, is a reclusive Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist who never gave the world a second novel. Forrester befriends a 16-year-old inner-city basketball player named Jamal. Jamal, an aspiring writer, visits Forrester’s apartment to seek the author’s wisdom. In one scene, Forrester and Jamal have a lively discussion about writing rules, such as “You shouldn’t start a sentence with ‘and.'” They talk about how breaking the rules can create a significant impact. If overdone, however, it also can have a devastating effect.

This is so true in photography. Photographers must study and know the rules of good visual composition like writers study and learn the rules of good writing composition. Once you understand the rules, your ability to break them helps you have a better impact on your photos.

[NIKON D2X, 18.0-125.0 mm f/3.3-5.6, ISO 100, ƒ/5.6, 1/90, Focal Length = 187]

Breaking the rules can create visual surprises. Tom Kennedy was the director of photography for National Geographic magazine when I showed him my portfolio many moons ago. While my work was professional and of excellent quality at the time, Kennedy commented that he wanted more surprises.

Kennedy had seen just about everything in his role at National Geographic. When Kennedy said he wanted to see more surprises, he wanted — for example — to see shots that weren’t taken from my average standing or sitting height. One of the things his critique had me doing right away was looking for the extreme. I started shooting with my camera on the ground and finding ways to get up high. I also started to shoot extreme close-ups, another change in what I’d been doing.

[NIKON D2X, AF Zoom 18-50mm f/2.8G, ISO 100, ƒ/6.3, 1/90, Focal Length = 27]

There comes the point in your photographic journey where you begin to find your voice. In the movie, Forrester had Jamal use a typewriter to copy Forrester’s work simply. The author started doing this after he set down a typewriter in front of Jamal, and the pupil just sat there waiting for something to come into his head. When Forrester saw Jamal wasn’t typing, he asked Jamal, “What are you doing?”

“I am thinking,” said Jamal.

“No thinking,” Forrester replied. “That comes later.”

Forrester gave him some of his work to copy to get the juices flowing. Through punching the keys and going through the actions, Jamal loosened up and slowly, after copying the job, started to write his work.

Photographers do the same thing. We copy other people’s work to learn how they did it and then add the underlying technology to our long-term memory to use later. Most arts require mastering specific skills before you can create your original works. This typically takes about five years. You can see this as musicians learn to play an instrument like a piano.

After copying the concepts of other photographers, you soon learn that your work is no better or worse than many others. This is when you realize that to stand out from others, you must do something unique — your surprise.

Forrester had a great quote that made me think; he asked, “Why is it the words we write for ourselves are always so much better than the words we write for others?” As photographers, we don’t always receive assignments that challenge us; there’s only so much you can do with a check presentation, for example. Most of the great photographers I know have a secret to their work — personal projects that sustain their creative juices.

The key to surprising others is first to surprise yourself — to take risks and look through your camera differently, not being afraid to break the rules. Stretch your way of looking and see if there is a better perspective than you usually take when taking photos. Who knows what you might discover?